Files

Download Full Text (2.8 MB)

Date Original

1939 September 1

Description

This document was written by Walter Rowland, who was a writer for the Federal Writers' Project under the Works Projects Administration. This document discusses the Lithuanian community in Arkansas, when they came into Arkansas, and where they settled, and includes a biographical sketch of a Lithuanian man named Petrolas, discussing his life in Lithuania and his move to the United States.

Biographical/Historical Note

The Works Progress Administration, which became the Work Projects Administration (WPA), was the largest and most ambitious of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal agencies. The Arkansas Federal Writer's Project was the part of the WPA that was created to focus on the history of Arkansas as part of the American Guide series. Publications such as these would give points of interest from each state, covering topics of agriculture, geography and geology, history, Indians, industry, place names, immigration, and transportation. The Work Projects Administration's final report for Arkansas was completed on March 1, 1943. During its operations it expended more than $116,000,000 on employment programs, paved over 11,000 miles of roads, built over 600 new public schools, and repaired many others.

Transcription

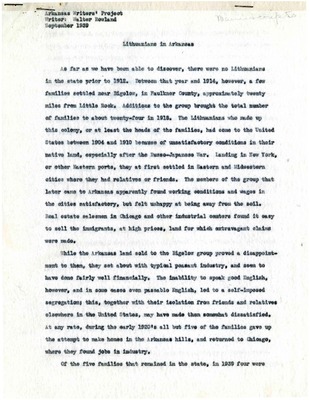

Arkansas Writers' Project

Writer: Walter Rowland

September 1939

Lithuanians in Arkansas

As far as we have been able to discover, there were no Lithuanians

in the state prior to 1912. Between that year and 1914, however, a few

families settled near Bigelow, in Faulkner County, approximately twenty

miles from Little Rock. Additions to the group brought the total number

of families to about twenty-four in 1918. The Lithuanians who made up

this colony, or at least the heads of the families, had come to the United

States between 1904 and 1910 because of unsatisfactory conditions in their

native land, especially after the Russo-Japanese War. Landing in New York,

or other Eastern ports, they at first settled in Eastern and Midwestern

cities where they had relatives or friends. The members of the group that

later came to Arkansas apparently found working conditions and wages in

the cities satisfactory, but felt unhappy at being away from the soil.

Real estate salesmen in Chicago and other industrial centers found it easy

to sell the immigrants, at high prices, land for which extravagant claims

were made.

While the Arkansas land sold to the Bigelow group proved a disappoint-

ment to them, they set about with typical peasant industry, and seem to

have done fairly well financially. The inability to speak good English,

however, and in some cases even passable English, led to a self-imposed

segregation; this, together with their isolation from friends and relatives

elsewhere in the United States, may have made them somewhat dissatisfied.

At any rate, during the early 1920's all but five of the families gave up

the attempt to make homes in the Arkansas hills, and returned to Chicago,

where they found jobs in industry.

Of the five families that remained in the state, in 1939 four were

living on rural mail route number 2, out of Bigelow. The fifth family

has a farm and service station on State Highway 10, about fourteen miles

northwest of Little Rock.

All five of the families have a love of farming, and seem frugal and

industrious. Their small vineyards furnish enough wine for home use. (An

Italian settlement near Bigelow sells wine that enjoys a state-wide reputa-

tion.) They do not rely heavily on cash crops, but instead are firm be-

lievers in subsistence farming. They grow their own vegetables, kill their

own meat, and can both types of food.

The family heads are Roman Catholic, and attend church when services

and transportation are available at the same time. The children remain in

the same faith, though perhaps they are not as firmly attached to it; this

is partly because they are on an Arkansas "mission", and there is no resi-

dent priest, or opportunity to attend mass regularly.

In the homes Lithuanian is spoken, because none of the parents speak

good English. In speech the children are bi-lingual, though they do not

read Lithuanian. Every family, however, subscribes to a Lithuanian news-

paper. The grandchildren probably will never learn Lithuanian, nor reveal

a trace of the accent in their talk. Some of the children farm; a few have

migrated to midwestern and northern cities.

In addition to the small group remaining near Bigelow, there is a

Lithuanian gardener living in North Little Rock. The farmer who lives on

State Highway 10 near Bigelow says that perhaps there are a few of his

countrymen in the coal mining district near Fort Smith, but it has not

been possible to ascertain the names or residences of such persons. Nor

has it been possible to verify the possibility that a Lithuanian farmer

resides in the vicinity of Ash Flat, near the residence of Maldo Arnold.

Attached to this note concerning the few Lithuanians Known, or thought,

to be in Arkansas, are two brief biographical sketches typical of mem-

bers of the Bigelow colony.

Arkansas Writers Project

Writer: Walter Rowland

September 1939

Lithuanian Biographical Sketch (1)

Petrolas was a short, stocky man with thick, work-roughened hands.

His blue eyes twinkled, and he occasionally removed a sweat-stained work

cap, revealing sandy hair. He was mowing hay, and called to his team in

English, though it was evident that even after this many years he was more

at home in his native tongue. Even so, he spoke better English than his

bulky wife, who made up for her lack of vocabulary by nodding and beaming

in support of all he said. Her face fairly glowed in the sun and she

laughed at everything. She showed a delighted enthusiasm, offering, for

example, to "run to the house" despite the heat so that we could see what

a Lithuanian paper was like.

He was born, he said, in 1883, near a little place called Radviliskis.

Their crops included wheat, oats, barley, rye and flax. Their home was a

log structure, chinked with moss, and almost unbelievably cold in the

winter. In the very worst weather the smoke from their great ovens-- as

big as an automobile, he insisted-- became so thick in the house that they

had to lie upon the floor to keep from choking. They made their own linen,

baked twenty-pound loaves of black rye bread, and did practically all their

work by hand, since they had few animals and no machines.

The Russo-Japanese Way left the country almost unlivable for the

Lithuanians. Their language was suppressed, or at least it was not taught;

there were "no schools, no newspapers, no nothing." The railroads were

tied up by strikes, and large numbers of Lithuanians were sent to Siberia.

The only employment was in the hated Russian factories, where a year's

wages might amount to twenty or twenty-five dollars.

In 1906 a cousin in American sent him a ticket. The ship docked in

Baltimore, "Md." A train took him to Philadelphia, where he had friends,

and they got him a job in a "shoogar" factory. It was as if a child were

given a job in Santa Claus' shop. Sugar had been a rare delicacy in the

old country, an almost unheard-of luxury; here it was as so much dirt.

Why, they would actually let the workers eat all they wanted! He ate it

by lumps and handfuls, he dissolved it in cold water and drank it. Truly

this America was a rich country, where a common worker might eat all the

precious sugar he could hold. He sadly told me that he didn't care much

for sugar now, and his wife doubled over at the gleeful remembrance of the

first time she got all the sugar she wanted.

Work in the sugar factory was satisfactory, but during the slack win-

ter season employment was often difficult to obtain, because of the numbers

of "young men" anxious to work at the prevailing wage of 15¢ an hour for a

twelve-hour day. Several of his best friends in Philadelphia died, and in

1908 he moved to Chicago, the American mecca of his race.

Continued association with foreign-born groups had kept him from

learning English well, but through Lithuanians in Chicago he obtained work

in the stockyards. After seven months he got a job in a tailor shop. At

first his pay was fifteen cents an hour; by gradual increase it rose to

thirty cents, but there was work "joost four or five" hours a day. His

fellow tailors organized and went on strike, going back to their machines

at the phenomenal wage of seventy cents an hour. He met his wife in Chicago

and they were married and began to save money. ("Yeah, Yeah!" she threw

up her hands and laughed all over.)

They lived in Chicago nearly ten years and saved enough to pay a slick-

tongued, Lettish-speaking salesman five or six times the value of the Ark-

ansas tract they bought. It was cleared, rich land, the richest in the

world, the salesman said, and would grow anything. When they came South

and the wife saw the brush-covered hillside that would grow anything she

wanted to give up and go back to Chicago.

The wife broke in, "I vanted [SIC] to go back, but he say no, you got to

stay, I vant [SIC] to farm," and they stayed. Both were strong-- she was not

fat then-- and they worked from morning till night chopping off the trees

and underbrush. They still had some money to buy seed and stock, and the

farm prospered.

Their home is fairly comfortable, differing little from their neigh-

bors' except perhaps it is cleaner. At first he tilled his fields with

Old World frugality and care, but now they look about like any in the vi-

cinity. The homeland touch is a small vineyard, from which he makes a few

gallons of wine each year.

In 1931 the government granted him a loan on his crop. Before that he

was shrewd enough to homestead eighty adjoining acres so that if a stock

law is passed he has land to fence for a pasture. Already he has the county

agent's promise to bring him some lespedesa seed to get his pasture started.

He watches the foreign situation rather closely and has predicted that

Lithuania will be gobbled up by Germany, a country for which he holds little

love. He and his wife have no children, which he considers just as well,

since children "don't like to live on farm nowadays."

A sick friend lived with them a long time without paying rent, and

when he died he left them his car, a late model Chevrolet. Neither Petrolas

nor his wife have the slightest idea how to run a car but he is going to

learn, because both are very fond of travel. Then, too, they can begin

going to the Roman Catholic church, a habit they dropped because the church

is some distance from their home.

When Petrolas came to Arkansas he was cheated on prices a few times.

But a Lithuanian peasant learns quickly; he does very well in his trades now,

and all in all, is quite content. The cities have too many cars and too

much gas to be healthful, he says. Last fall he returned to Chicago for

a six weeks visit, and found that a number of his friends had died. In

Arkansas people get vegetables and milk, butter and meat, fit food for

those whose ancestors have farmed for generations. He is fifty-six, strong

and hearty, still able to do a day's work with ease. "We be dead long ago

I'm sure if we don't live here. Arkansas is healthy," he said, and his

wife commented that though she was fat she never hurt any and could still

do plenty of work.

He is proud of being a citizen. It is their bulwark against European

difficulties. He says that since he is a citizen nobody can make him go

back, and nobody can take his farm away from him. When asked if he liked

Arkansas he answered, "Shoore; if we no like it here we move," and his wife

shook with merriment.

Physical Description

Document, 8" x 10.5"

Subjects

Works Projects Administration; Lithuanian Community; Immigrants

Geographical Area

Bigelow, Faulkner County (Ark.)

Language

English

Identifier

MS.000567, Box 6, Folder 76, Item 1

Collection

Works Progress/Work Projects Administration (WPA) Arkansas research files, MS.000567

Publisher

Arkansas State Archives

Contributing Entity

Arkansas State Archives

Recommended Citation

Arkansas Federal Writer's Project: "Lithuanians in Arkansas", Works Progress/Work Projects Administration (WPA) Arkansas research files, Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Rights

Use and reproduction of images held by the Arkansas State Archives without prior written permission is prohibited. For information on reproducing images held by the Arkansas State Archives, please call 501-682-6901 or email at state.archives@arkansas.gov.

Preview